Scientists have been studying the exoplanet TRAPPIST-1 e. Could it harbor alien life?

1. Catchy Headline

Is Earth 2.0 a Mirage? New Data on TRAPPIST-1e Reshapes the Hunt for Alien Life

2. Brainx Perspective (Intro)

At Brainx, we believe the recent findings regarding TRAPPIST-1e serve as a crucial reality check for modern astronomy. This development highlights that finding a “second Earth” requires more than just locating a rocky planet in a star’s habitable zone; it demands a deeper understanding of atmospheric resilience and cosmic durability. The search for life is not merely a game of coordinates, but a complex puzzle of planetary evolution.

3. The News (Body)

For years, humanity has pinned its hopes on a specific cosmic neighbor in the search for extraterrestrial life: TRAPPIST-1e. Located just 40 light-years away, this Earth-sized world seemed to possess all the right ingredients for habitability. However, a groundbreaking new study has shattered these optimistic assumptions, forcing scientists to rethink what makes a planet truly “livable.”

The Goldilocks Dilemma: What We thought We Knew

The search for life has traditionally revolved around the “Goldilocks Zone”—the specific distance from a star where temperatures are neither too hot nor too cold, allowing liquid water to exist. TRAPPIST-1e sits perfectly within this zone. However, the latest data suggests that location is only a fraction of the battle.

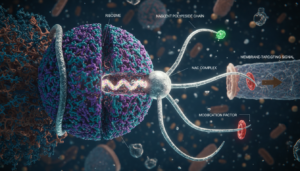

To support life as we know it, a planet requires a “Cosmic Checklist” of ingredients:

- The Right Mass: A planet must be large enough to generate gravity strong enough to hold onto an atmosphere.

- A Protective Atmosphere: This is the planet’s shield. It regulates surface temperature (the greenhouse effect) and protects living organisms from deadly cosmic radiation.

- Liquid Water: The universal solvent required for biochemical reactions.

- Internal Activity: Geological activity, like a magnetic field generated by a molten core, is essential to deflect stellar winds that would otherwise strip away the atmosphere.

The TRAPPIST-1e Disappointment

The TRAPPIST-1 system, an ultra-cool dwarf star hosting seven Earth-sized planets, was viewed as the “Holy Grail” of exoplanet research. TRAPPIST-1e was the standout candidate—rocky, Earth-sized, and temperate.

However, recent findings published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters paint a starkly different picture:

- Atmospheric Void: Using advanced transit data (analyzing how light changes as the planet passes its star), researchers found no significant absorption features. This indicates that TRAPPIST-1e likely has a negligible or non-existent atmosphere.

- Radiation Exposure: Without an atmosphere, the surface of the planet would be bombarded by harsh stellar radiation, making complex life on the surface nearly impossible.

- Water Loss: Without an atmospheric blanket to provide pressure and temperature regulation, liquid water cannot exist stably on the surface; it would either boil away into space or freeze solid.

The “Red Dwarf” Problem

This discovery highlights a major hurdle in exoplanetary science. TRAPPIST-1 is an M-dwarf star (Red Dwarf). While these stars are the most common in the galaxy, they are also incredibly violent in their youth.

- Stellar Flares: Red dwarfs emit massive flares of radiation that can strip the atmospheres off of nearby planets.

- Tidal Locking: Planets in the habitable zone of these dim stars must orbit very close, often leading to “tidal locking,” where one side of the planet permanently faces the star (scorching hot) and the other faces away (freezing cold).

Refocusing the Search: The New Strategy

The disappointment of TRAPPIST-1e is not a defeat; it is a lesson. Astronomers are now pivoting their strategies to ensure future resources are spent on the most viable targets.

Key Shifts in Exoplanet Research:

- Atmospheric Characterization First: Rather than assuming habitability based on size and distance, the priority is now to detect an atmosphere first. Tools like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are being tasked with hunting for specific biosignatures (methane, oxygen, carbon dioxide).

- Looking Beyond Red Dwarfs: Scientists are broadening the search to stars more like our Sun (G-type stars) or slightly cooler K-type stars, which are more stable and less likely to strip their planets of air.

- Subsurface Potential: The definition of “habitable” is expanding to include “Ocean Worlds.” Scientists are looking at moons (like Europa and Enceladus in our own solar system) that may harbor vast oceans of liquid water beneath thick crusts of ice, protected from radiation without needing an atmosphere.

4. “Why It Matters” (Conclusion)

This recalibration of the search for life saves valuable time and resources, steering humanity away from “mirage” planets. For the common man, it deepens our appreciation for Earth’s rarity; we live on a fragile oasis protected by a thin blue line that, as TRAPPIST-1e proves, is far from guaranteed in the cosmos.

Leave a Reply